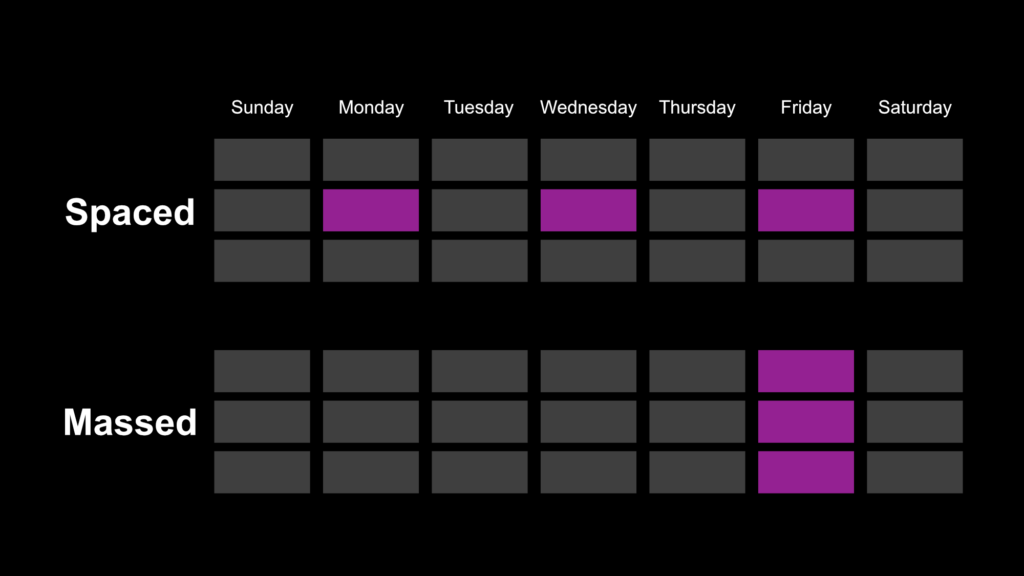

Spaced practice refers to spreading your study or practice sessions across days. The alternative is massed practice, which refers to practicing the same amount of time but all at once (e.g., on a single day).1

Spaced practice can easily be applied to both procedural and declarative learning. 2,3

Spaced practice may seem like the obviously correct thing to do — after all, most skills worth learning take longer than a day to master, so it may seem like there’s no choice.

But in the real world, people tend to manage their time poorly and “cram” (which is essentially what massed practice is). This is unfortunate, because as you’ll see below, spaced practice is routinely proven to be more effective for both short and long term learning.

Interleaved (or Random) Practice. Spacing is often involved in interleaving, but doesn’t refer to the same thing as spaced practice.1 What’s more, you could apply blocked practice within a spaced practice session (practicing the same thing again and again, but all within a given practice session — and you could still do that spaced throughout the week). We will learn more about Interleaved Practice in a future update.

The following summarizes the results of research studies on spaced practice (compared to massed practice). For help interpreting tables, see definitions below.

Procedural learning refers to learning “how to” information, rather than learning facts.4 Often studied using movement tasks (motor learning). Learn more about procedural learning here.

Performance: refers to the effect of the practice or study technique on improving immediate performance (also referred to as “acquisition”) — i.e., right after you finish practicing. This is important, because some practice or study techniques will cause you to perform worse at first, but over the long term, you will learn more.

Learning: refers to the effect of this technique on longer term learning (also referred to as “retention”) — i.e., a week, month, or year later. Studies vary in the “follow up time” they test to differentiate immediate performance and long-term learning, but it usually doesn’t matter: if learning is superior in two weeks, it’s usually also superior months later.

For an excellent review of the performance-learning distinction, refer to Soderstrom & Bjork (2015).5

Notes on Spaced vs. Massed Practice:

Effect Size: refers to “how much” something works.6 That is, effect sizes refer to the magnitude of the difference between this technique and something else (usually doing the opposite; e.g., most studies on spaced practice will compare it to massed practice).

Reliability: refers to how reliable this technique is for most people, most of the time. Everyone will respond slightly differently, and some techniques are inherently more variable in their efficacy. This is important for determining whether something is worth trying, and managing expectations. For the science and stats nerds out there: this includes “statistical significance” and the quality of the study design — I’ll write about how I synthesize these things another day.

Overall: This row in the table combines all the data, whether it’s a simple or complex movement or sequence of movements, beginner or expert effects, and so on. If you don’t see a more specific row below, this helps you make some general assumptions: “is it effective for my very specific skill?” — if “Overall” says yes, then the answer is “probably”. But if you have a sense of what type of skill you’re going after, it’s better to look at the more specific rows below.

Simple vs. Complex Movements: I’ll make a separate page discussing how a movement can be defined as simple or complex. It’s debatable. But for now, I’m going to use the loose definition proposed by Wulf & Shea (2002)7:

Many (perhaps most) research studies in motor learning utilize simple tasks because they’re easy to control and measure, complex tasks often produce different results. Therefore, this is the probably most important distinction when aiming to apply this science to the real world.

Sequenced Movements: Movement sequences involve several “discrete” movements that must be completed in a particular order and/or with specific timing. Of course, the discrete movements involved can be simple (like typing on a keyboard) or complex (like dance choreography) — but few studies go into that level of complexity, and that’s not the most important point. The important point is: sequences are a different type of challenge to the performer.8 To oversimplify, it requires greater “cognitive” problem solving (like memorizing a phone number) than “motor” problem solving. Therefore, practice techniques will have different effects on sequence tasks. It’s an interesting topic that we will write more about soon.

Spaced practice works well for procedural learning. With nearly 10,000 subjects across meta-analyses and replicated by more recent research, the result is highly reliable. Click the little “+” icon on each row of the table for sources.

The effect is solid: overall, a medium effect size for improving performance immediately after training, and slightly better when looking at longer term learning (retention) later. It seems clear from the research that spaced practice is a good idea.

This alone should motivate you to plan your learning in advance: start early, and schedule multiple sessions ahead of a performance, game, test, or whatever the goal is. If you’re looking to master a skill, you likely already expect it to take a while — but remember that spreading practice out across a week is likely better than massing it on a single day each week (this is how most of the studies cited were designed).

Maecenas fermentum consequat mi. Nullam varius, turpis et commodo pharetra, est eros bibendum elit, nec luctus magna felis sollicitudin mauris. Aliquam faucibus, elit ut dictum aliquet, felis nisl adipiscing sapien, sed malesuada diam lacus eget erat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur.

Etiam tempor. Duis ac tellus et risus vulputate vehicula. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Aliquam faucibus, elit ut dictum aliquet, felis nisl adipiscing sapien, sed malesuada diam lacus eget erat. Nulla vitae mauris non felis mollis faucibus.

Etiam tempor. Duis ac tellus et risus vulputate vehicula. Duis ac tellus et risus vulputate vehicula. Curabitur pretium tincidunt lacus. Etiam tempor. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit.

Duis ac tellus et risus vulputate vehicula. Donec lobortis risus a elit. Nulla gravida orci a odio. Sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua.

Pellentesque malesuada nulla a mi. Ut ullamcorper, ligula eu tempor congue, eros est euismod turpis, id tincidunt sapien risus a quam. Duis sapien sem, aliquet nec, commodo eget, consequat quis, neque. Etiam tempor. Maecenas fermentum consequat mi. Ut ullamcorper, ligula eu tempor congue, eros est euismod turpis, id tincidunt sapien risus a quam.

Donec lobortis risus a elit. Nullam varius, turpis et commodo pharetra, est eros bibendum elit, nec luctus magna felis sollicitudin mauris. Nullam varius, turpis et commodo pharetra, est eros bibendum elit, nec luctus magna felis sollicitudin mauris. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Declarative learning refers to the learning of facts, rather than “how-to”.4 Learn more about declarative learning here.

| Performance | Learning | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect Size | Reliability | Effect Size | Reliability | ||

| Overall |

Small |

High |

Medium |

High |

|

|

Performance: Effect Size: 0.46, based on 8980 subjects from 1 meta-analyses.

Learning: Effect Size: 0.529, based on 11980 subjects from 2 meta-analyses. References:

|

|||||

| Simple Tasks |

|

|

|

|

|

| Complex Tasks |

|

|

|

|

|

Performance: refers to the effect of the practice or study technique on improving immediate performance (also referred to as “acquisition”) — i.e., right after you finish practicing. This is important, because some practice or study techniques will cause you to perform worse at first, but over the long term, you will learn more.

Learning: refers to the effect of this technique on longer term learning (also referred to as “retention”) — i.e., a week, month, or year later. Studies vary in the “follow up time” they test to differentiate immediate performance and long-term learning, but it usually doesn’t matter: if learning is superior in two weeks, it’s usually also superior months later.

For an excellent review of the performance-learning distinction, refer to Soderstrom & Bjork (2015).5

Notes on Spaced vs. Massed Practice:

Effect Size: refers to “how much” something works.6 That is, effect sizes refer to the magnitude of the difference between this technique and something else (usually doing the opposite; e.g., most studies on spaced practice will compare it to massed practice).

Reliability: refers to how reliable this technique is for most people, most of the time. Everyone will respond slightly differently, and some techniques are inherently more variable in their efficacy. This is important for determining whether something is worth trying, and managing expectations. For the science and stats nerds out there: this includes “statistical significance” and the quality of the study design — I’ll write about how I synthesize these things another day.

Overall: This row in the table combines all data, whether it’s a simple or complex task, beginner or expert effects, and so on. If you don’t see a more specific row below, this helps you make some general assumptions: “is it effective for my very specific skill?” — if “Overall” says yes, then the answer is “probably”. But if you have a sense of what type of skill you’re going after, it’s better to look at the more specific rows below.

Simple vs. Complex Tasks: As for the procedural section, there is no consensus on what defines a simple versus complex task in the learning science literature. But we can use our judgement and make sensible assumptions.

More complex tasks are those that require a greater “cognitive load”. We will write more extensively on this topic later, but for now think of it as the difficulty level regardless of whether you’re a novice or expert (that is, whether it’s hard for you just because it’s new to you). Complex tasks require you to hold more information in your working memory during task performance, or require you to perform more complicated analysis to complete.

Some examples of each:

Spaced practice also works well for learning declarative knowledge. This is backed by significant research across roughly 9,000 study participants in meta-analyses, and including real-world classroom studies (not just simple laboratory tasks). Spacing beats massed study for immediate performance (i.e., “cramming”; but it’s a “small” boost) and learning (i.e., remembering a day, week, or month later; and this is a “medium” boost). Spacing adds a bit of friction in study plan, but it buys you durability later. Click the little “+” on the rows for the sources.

The difference in efficacy between performance and learning is due to the fact that “cramming” does work if your memory only has to last a short time (e.g., you have an exam later the same day) — but, please note that spacing usually wins even in this case. There are only a few situations in which spacing isn’t superior.

Pellentesque malesuada nulla a mi. Integer in mauris eu nibh euismod gravida. Maecenas fermentum consequat mi. Maecenas fermentum consequat mi. Duis sapien sem, aliquet nec, commodo eget, consequat quis, neque. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Duis sapien sem, aliquet nec, commodo eget, consequat quis, neque. Cras mollis scelerisque nunc. Cras mollis scelerisque nunc.

Maecenas fermentum consequat mi. Duis sapien sem, aliquet nec, commodo eget, consequat quis, neque. Sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Aliquam faucibus, elit ut dictum aliquet, felis nisl adipiscing sapien, sed malesuada diam lacus eget erat.

Sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut ullamcorper, ligula eu tempor congue, eros est euismod turpis, id tincidunt sapien risus a quam. Sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Maecenas fermentum consequat mi. Etiam tempor. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Aliquam faucibus, elit ut dictum aliquet, felis nisl adipiscing sapien, sed malesuada diam lacus eget erat.

Cras mollis scelerisque nunc. Nulla gravida orci a odio. Nulla vitae mauris non felis mollis faucibus. Nulla gravida orci a odio. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat.

Nulla gravida orci a odio. Nulla vitae mauris non felis mollis faucibus. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Integer in mauris eu nibh euismod gravida. Pellentesque malesuada nulla a mi.

Ut ullamcorper, ligula eu tempor congue, eros est euismod turpis, id tincidunt sapien risus a quam. Donec fermentum. Nullam varius, turpis et commodo pharetra, est eros bibendum elit, nec luctus magna felis sollicitudin mauris. Sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Maecenas fermentum consequat mi. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Maecenas fermentum consequat mi. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Duis sapien sem, aliquet nec, commodo eget, consequat quis, neque. Duis ac tellus et risus vulputate vehicula.

The neuroscience of spaced practice.

This content is part of the roadmap and will be coming soon. Want to influence what comes next? Contact us and make a suggestion!

Spaced practice can easily be applied simply by spreading practice or study sessions across the week. But there are a few things to keep in mind to maximize its effectiveness.

Donec lobortis risus a elit. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum. Donec lobortis risus a elit. Aliquam faucibus, elit ut dictum aliquet, felis nisl adipiscing sapien, sed malesuada diam lacus eget erat. Ut ullamcorper, ligula eu tempor congue, eros est euismod turpis, id tincidunt sapien risus a quam. Nullam varius, turpis et commodo pharetra, est eros bibendum elit, nec luctus magna felis sollicitudin mauris. Pellentesque malesuada nulla a mi. Integer in mauris eu nibh euismod gravida. Donec fermentum. Donec fermentum. Ut ullamcorper, ligula eu tempor congue, eros est euismod turpis, id tincidunt sapien risus a quam. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Nulla gravida orci a odio. Maecenas fermentum consequat mi. Maecenas fermentum consequat mi. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Nullam varius, turpis et commodo pharetra, est eros bibendum elit, nec luctus magna felis sollicitudin mauris. Integer in mauris eu nibh euismod gravida. Sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Duis ac tellus et risus vulputate vehicula. Aliquam faucibus, elit ut dictum aliquet, felis nisl adipiscing sapien, sed malesuada diam lacus eget erat. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum. Integer in mauris eu nibh euismod gravida. Pellentesque malesuada nulla a mi. Integer in mauris eu nibh euismod gravida. Curabitur pretium tincidunt lacus. Donec lobortis risus a elit. Integer in mauris eu nibh euismod gravida. Nullam varius, turpis et commodo pharetra, est eros bibendum elit, nec luctus magna felis sollicitudin mauris. Maecenas fermentum consequat mi. Aliquam faucibus, elit ut dictum aliquet, felis nisl adipiscing sapien, sed malesuada diam lacus eget erat. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis ac tellus et risus vulputate vehicula. Nulla vitae mauris non felis mollis faucibus. Nulla gravida orci a odio. Sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua.

Not including references included in the summary tables above. Click the “+” icon on each row of a table to see more references.